---

Samantha Cooke sits silently on her couch waiting for the phone to ring.

---

Her eyes drift from her phone to her son, Anthony, who is lying in front of her on his favorite blue blanket. Normally energetic, this vibrant one-year-old, who was walking and crawling everywhere just a mere few weeks ago, cannot so much as move his neck or back.

“Sit up for Mama, Anthony." Samantha softly says to him hoping by some miracle that he turns towards her, but she gets no response.

The stark contrast of the memory he was just a few weeks ago brings a familiar lump in Samantha’s throat. As she waits, she recollects the unpleasant journey that brought them here.

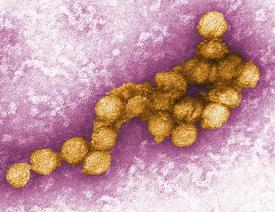

The Cookes had just moved months before to the lakeside community. The close proximity of the lake attracted the new family to the property. It didn’t matter that their new Victorian house was in dire need of work; the location alone was worth it. Along with the rest of their neighbors, the Cooke’s enjoyed picnics, barbeques, and various outdoor activities during the hot summer days. During all these activities, Samantha couldn’t help but notice signs posted by the health department warning people of the dangers of drowning, excess sun exposure and the West Nile virus (WNV). West Nile virus had been in the news lately because of the increase in the number of cases seen in surrounding towns.

“Sit up for Mama, Anthony." Samantha softly says to him hoping by some miracle that he turns towards her, but she gets no response.

The stark contrast of the memory he was just a few weeks ago brings a familiar lump in Samantha’s throat. As she waits, she recollects the unpleasant journey that brought them here.

The Cookes had just moved months before to the lakeside community. The close proximity of the lake attracted the new family to the property. It didn’t matter that their new Victorian house was in dire need of work; the location alone was worth it. Along with the rest of their neighbors, the Cooke’s enjoyed picnics, barbeques, and various outdoor activities during the hot summer days. During all these activities, Samantha couldn’t help but notice signs posted by the health department warning people of the dangers of drowning, excess sun exposure and the West Nile virus (WNV). West Nile virus had been in the news lately because of the increase in the number of cases seen in surrounding towns.

“Is West Nile virus a problem here?” Samantha remembers asking her neighbor, Sally, one afternoon after hearing about another West Nile case on the news.

“Not really," Sally replied. The health department monitors the mosquitoes in the area for that virus. Can you believe they trap mosquitoes? Take them all, that’s what I say!”

Samantha laughed, and then Sally continued. “Every year they put out these mosquito traps all over the place. I talked to one of the people setting the traps, and she said they were doing surveillance. They bring the mosquitoes from the traps back to the lab where they identify and test them for the virus. And you know that chicken coop down the road? Those chickens are property of the health department! They test blood from the chickens for surveillance, too. I guess the virus doesn’t kill chickens, but dead birds are a telltale sign of the virus. I haven’t seen any, have you?”

“No," said Samantha. "But there are a lot of mosquitoes here, that's for sure. I keep spraying Anthony and me with bug repellent, but by the end of the day, I always manage to miss a spot or two on both of us.”

“Well, they are attracted to water," continued Sally. "It is just a price you pay for living so close to it. But I wouldn’t worry about it. From what I hear, WNV doesn’t really cause much of an illness in people, anyway. Just have the repellents on hand and cover up as much as you can bear it to avoid the mosquitoes."

“Not really," Sally replied. The health department monitors the mosquitoes in the area for that virus. Can you believe they trap mosquitoes? Take them all, that’s what I say!”

Samantha laughed, and then Sally continued. “Every year they put out these mosquito traps all over the place. I talked to one of the people setting the traps, and she said they were doing surveillance. They bring the mosquitoes from the traps back to the lab where they identify and test them for the virus. And you know that chicken coop down the road? Those chickens are property of the health department! They test blood from the chickens for surveillance, too. I guess the virus doesn’t kill chickens, but dead birds are a telltale sign of the virus. I haven’t seen any, have you?”

“No," said Samantha. "But there are a lot of mosquitoes here, that's for sure. I keep spraying Anthony and me with bug repellent, but by the end of the day, I always manage to miss a spot or two on both of us.”

“Well, they are attracted to water," continued Sally. "It is just a price you pay for living so close to it. But I wouldn’t worry about it. From what I hear, WNV doesn’t really cause much of an illness in people, anyway. Just have the repellents on hand and cover up as much as you can bear it to avoid the mosquitoes."

The Cookes spent a good deal of time that summer outside and continued to do so into the fall months. By then, talks of WNV faded along with the summer.

Then in late September, in a grim turn of events, Anthony became noticeably ill. Samantha is alarmed that Anthony is fever ridden, but quickly dismisses it because of his teething. But when Anthony, the normally energetic baby, becomes increasingly lethargic and does not eat, Samantha decides it would be a good idea to take him to the doctor.

The visit goes by quickly. The fever is down and the symptoms are attributed to the Samantha’s initial thought- teething. Relieved and hopeful that Anthony is on his way back to normal, Samantha thanks the doctor and she and Anthony make their way home.

Unfortunately, on their way home the relief disappears. Samantha hears a thud and assumes it is something she hit in the road. Then she catches a glimpse of Anthony in the rearview mirror shaking violently.

Then in late September, in a grim turn of events, Anthony became noticeably ill. Samantha is alarmed that Anthony is fever ridden, but quickly dismisses it because of his teething. But when Anthony, the normally energetic baby, becomes increasingly lethargic and does not eat, Samantha decides it would be a good idea to take him to the doctor.

The visit goes by quickly. The fever is down and the symptoms are attributed to the Samantha’s initial thought- teething. Relieved and hopeful that Anthony is on his way back to normal, Samantha thanks the doctor and she and Anthony make their way home.

Unfortunately, on their way home the relief disappears. Samantha hears a thud and assumes it is something she hit in the road. Then she catches a glimpse of Anthony in the rearview mirror shaking violently.

Panic-stricken, Samantha pulls over the side of the road phone and calls her husband Steve.

“Something is wrong with Anthony! He is shaking uncontrollably! I don’t what to do!” she cries.

“Take him back to the doctor, I will meet you there," says Steve.

The experience at the doctor’s is very different than it was less than an hour ago. This time around, Anthony’s condition is deemed severe and he is immediately transferred to the county children’s hospital. At the hospital, Samantha is given a long form to fill out during the wait and gives it back to the receptionist once complete. After waiting what seems like several hours in the waiting room, a nurse finally greets them and ushers Samantha and Steven into an office where a Dr. Shepard, the neurologist, is waiting for them.

Dr. Shepard describes Anthony’s grim condition as Samantha sits numb and speechless next to Steve for what seems like an eternity, only able to process his key points.

“Something is wrong with Anthony! He is shaking uncontrollably! I don’t what to do!” she cries.

“Take him back to the doctor, I will meet you there," says Steve.

The experience at the doctor’s is very different than it was less than an hour ago. This time around, Anthony’s condition is deemed severe and he is immediately transferred to the county children’s hospital. At the hospital, Samantha is given a long form to fill out during the wait and gives it back to the receptionist once complete. After waiting what seems like several hours in the waiting room, a nurse finally greets them and ushers Samantha and Steven into an office where a Dr. Shepard, the neurologist, is waiting for them.

Dr. Shepard describes Anthony’s grim condition as Samantha sits numb and speechless next to Steve for what seems like an eternity, only able to process his key points.

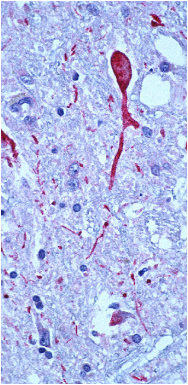

“Anthony is showing signs of meningoencephalopathy, and acute flaccid paralysis...”

“...might not be able to move neck or walk...”

“...likely from West Nile virus...”

“...youngest I’ve seen with this severe form of disease...”

“...will collect spinal fluid and send to state laboratory for a confirmatory test...”

“...might not be able to move neck or walk...”

“...likely from West Nile virus...”

“...youngest I’ve seen with this severe form of disease...”

“...will collect spinal fluid and send to state laboratory for a confirmatory test...”

Samantha is shaking her head in disbelief and starts crying as the doctor paints an ominous picture of what the future holds for Anthony.

“Anthony will need to come in daily to receive therapy to loosen his joints. The hope is that he will be able to walk again. But do understand, with the severity of this illness, it is only a hope, not a guarantee.”

Anthony stays at the hospital for a few days before he is released.

At the hospital, blood and cerebral spinal fluid is collected and sent to the state laboratory.

“Anthony will need to come in daily to receive therapy to loosen his joints. The hope is that he will be able to walk again. But do understand, with the severity of this illness, it is only a hope, not a guarantee.”

Anthony stays at the hospital for a few days before he is released.

At the hospital, blood and cerebral spinal fluid is collected and sent to the state laboratory.

The state laboratory receives Anthony’s sample to determine if it is positive for WNV. During the summer to fall months, the laboratory is inundated with samples destined for WNV testing. The test they perform on patient samples has a relatively simple concept behind how it works: has the patient’s immune system seen the virus?

Among many of the samples submitted to the laboratory, the results are definitive. The laboratory notifies the hospital as well as the state epidemiologists of the results. The hospital notifies the patient, whereas the epidemiologists use the information obtained from the state laboratory to aid in surveillance for overall safety of the public health

The phone finally rings and Samantha is quickly brought back to the present.

“Hello?”

"Is this Mrs. Garnett?"

“Yes, is this Dr. Shepard? Do you have the results?”

“Yes, I do. The state lab confirmed thatAnthony’s spinal fluid is WNV. Anthony has West Nile meningoencephalitis, one of the more severe form of the disease.“

With that, the doctor concludes with asking how Anthony is doing and then hangs up.

With the closure that comes with confirmation, Samantha looks back over at Anthony who lies motionless gazing at the ceiling. The lump forms again in her throat as she says in disbelief “all this because of a mosquito."

Among many of the samples submitted to the laboratory, the results are definitive. The laboratory notifies the hospital as well as the state epidemiologists of the results. The hospital notifies the patient, whereas the epidemiologists use the information obtained from the state laboratory to aid in surveillance for overall safety of the public health

The phone finally rings and Samantha is quickly brought back to the present.

“Hello?”

"Is this Mrs. Garnett?"

“Yes, is this Dr. Shepard? Do you have the results?”

“Yes, I do. The state lab confirmed thatAnthony’s spinal fluid is WNV. Anthony has West Nile meningoencephalitis, one of the more severe form of the disease.“

With that, the doctor concludes with asking how Anthony is doing and then hangs up.

With the closure that comes with confirmation, Samantha looks back over at Anthony who lies motionless gazing at the ceiling. The lump forms again in her throat as she says in disbelief “all this because of a mosquito."